Elevator pitch

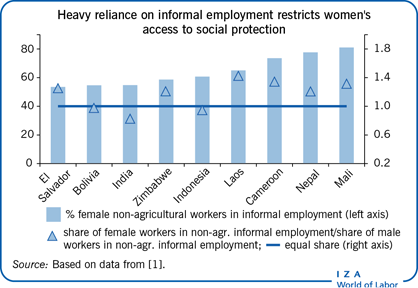

Women are more likely than men to work in the informal sector and to drop out of the labor force for a time, such as after childbirth, and to be impeded by social norms from working in the formal sector. This work pattern undermines productivity, increases women's vulnerability to income shocks, and impairs their ability to save for old age. Many developing countries have introduced social protection programs to protect poor people from social and economic risks, but despite women's often greater need, the programs are generally less accessible to women than to men.

Key findings

Pros

Social protection programs designed with women in mind have reached even very vulnerable and marginalized women.

Employment guarantee programs can be made more attractive to women by offering work close to home, flexible work hours, and childcare.

Flexible eligibility requirements, child credits, and the use of unisex mortality tables improve some of the gender inequities in traditional pension schemes.

Micro-pension schemes that allow small, flexible contributions enable women working in the informal sector to save for old age.

Microfinance institutions have made it easier for women to use financial services, making saving or borrowing an ex post form of social protection.

Cons

Women’s reproductive role and social norms exclude many women from formal social protection programs.

Scaling up informal, community-level social protection programs for women can be difficult as the programs often rely on a network of highly motivated individuals that is difficult to replicate at scale.

Most women in the labor force are concentrated in the informal sector and so have limited access to pension schemes.

Although micro-pensions and defined contribution schemes are better value for women, these schemes place all the risk on individuals.

Many women lack access to financial markets and so find it hard to cope with income shocks.